So long mindless button mashing

It pays to embrace inventive controls — just asked Nintendo, Activision, MTV Games, and Electronic Arts. The latter of which did so using a traditional controller even when in 2007 it released Skate, a game that outsold Tony Hawk’s latest by 2 to 1. What’s more, Skate was available on three fewer systems.

It pays to embrace inventive controls — just asked Nintendo, Activision, MTV Games, and Electronic Arts. The latter of which did so using a traditional controller even when in 2007 it released Skate, a game that outsold Tony Hawk’s latest by 2 to 1. What’s more, Skate was available on three fewer systems.

The reason for its success is simple: more gratifying controls.

Unlike the once-pioneering Tony Hawk series that relies heavily on button mashing, Skate lets players capture the feeling of skateboarding by executing timed gestures onto dual thumbsticks, with little dependence on buttons. EA calls it “Flickit” controls.

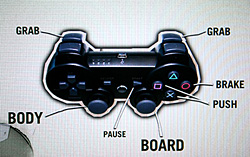

For example. The left stick controls body movement; the right stick controls board kicks. Left and right hand grabs can be performed by the left and right shoulder buttons, respectively. And left and right leg pushes are mapped to corresponding face buttons for forward movement. That’s it.

The result is significantly more rewarding and makes Tony Hawk controls feel like single-tail decks from the 80s. Simply put, landing a trick in Skate feels better than anything you’ll do in Hawk. Ironically, the control innovation was wrought by EA, a game-maker who is often criticized for merely updating its games like Madden NFL.

“It tricks your brain into thinking you could actually do it when you’re on a board,” says executive producer Scott Blackwood in an interview with EA. “Just like Guitar Hero, many of the guys playing this game forget that they can’t actually play a guitar. You’re lost in the moment, and it makes you want to skate.”

All of this is done with a standard controller of course — the Xbox 360/PS3 kind that sports 17 depressible buttons. It’s refreshing, almost comical then, to see Skate’s controller map before entering play. It lists just six specific functions, only four of which are needed to perform any trick (excluding the use of opposing limbs, which aren’t required). To put that into perspective, even a 17-year old SNES controller would have leftover buttons.

“[Conventional control schemes] are too artificial,” commented Clive Thompson in a 2007 Wired editorial, which praised Skate’s controls. “Game designers take organic, fluid, physical real-life movements and turn them into random, opaque button combinations… If controllers are too hard for newbies, maybe the solution is for designers to rethink how they’re used…” as Skate has effectively done.

If EA can break new ground using a default gamepad, anyone can.

Nintendo, for its part, took a radically different approach when rethinking control in 2006 when it released the motion-sensing Wii — so much in fact that the company marginalized the historical focus of a graphics upgrade in favor of user control. The Wii Remote has since created excitement, evolved appropriate genres like racers, sports and shooters, and made the Wii a breeding ground for interface experimentation. Oh, and it’s made Nintendo a fortune in the process, not to mention a return to the console top.

And then there are the rhythm-based games, which amplify immersion further still. Konami’s Dance Dance Revolution quietly started the craze in the late 90s. Guitar Hero then exploded the idea in homes across America in 2005, and MTV Games expanded the concept last year to include an entire band. Publishers are reaping the rewards, gamers have a new obsession, and wannabes can feel like rock stars thanks to convincing accessories. This is virtual reality.

Expectedly, all of the above mentioned examples have seen enormous commercial success, all because someone decided to enhance player control. Let that be a lesson to any aspiring developer.

At the very least, better controls will increasingly happen on all systems as a result of the added attention. Even if you’re indifferent to skating games, even if you shun the less-realistic graphics found on Wii, and even if you’re too prideful to try peripheral games, it doesn’t matter. The creativity will spill to other machines.

So be grateful. Your favorite games are going to benefit.–BLAKE SNOW

Great read Blake. I think you article was less complex than I originally thought it was going to be.

I have found that I don’t really care for complex button schemes anymore. I want something that if I don’t play for 10 years I can pick up and play without giving a second thought. Almost like riding a bike. I can’t even play games like Madden anymore because I have forgotten the button combos and its just not fun to learn them over again.

Maybe that is why people love old school nintendo games because they can pick it up 10 or 20 years later and still remember how to play the game.