Watch this comical video to see what I mean. Not everyone talks like this, of course, but a lot of companies do.

For whatever reason (usually cultural ones), businesses like to speak in code to each other, and then they pay me to decode the nonsense into something actual humans can understand in written form.

It’s a confusing phenomenon, but I ain’t complaining. I love doing it.

See also: Why corporate speak is garbage language

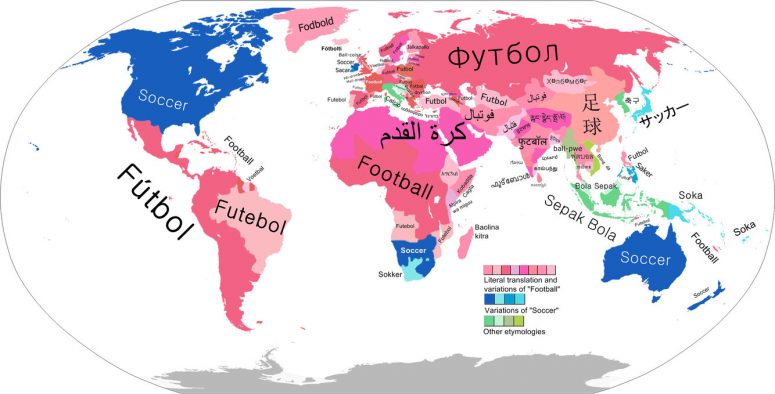

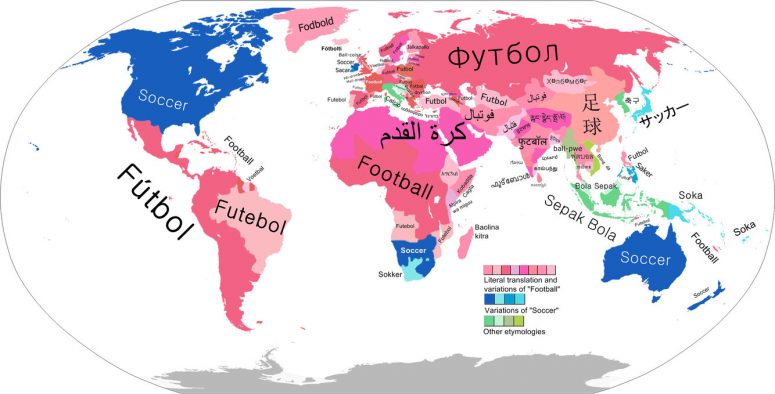

Courtesy Reddit

In fact, Irish, South Africans, Canadians, Australians, Kiwis, and even four-time World Cup champions Italy call the sport something other than “football.” In addition to America, the first five say “soccer,” while the latter call it “kick ball.”

As for how “soccer” got it’s name, the English actually invented it, according to the U.S. Embassy in London:

“Soccer’s etymology is not American but British. It comes from an abbreviation for Association Football, the official name of the sport. For obvious reasons, English newspapers in the 1880s couldn’t use the first three letters of Association as an abbreviation, so they took the next syllable, S-O-C. With the British penchant for adding ‘-er’ at the end of words—punter, footballer, copper, and rugger—the word ‘soccer’ was born, over a hundred years ago, in England, the home of soccer. Americans adopted it and kept using it because we have our own indigenous sport called football.”

There you have it. Don’t like the name “soccer,” blame the British.

Courtesy Warner Bros.

“For all of the other languages, the researchers discovered, the more data-dense the average syllable was, the fewer of those syllables had to be spoken per second — and thus the slower the speech. English, with a high information density of .91, was spoken at an average rate of 6.19 syllables per second. Mandarin, which topped the density list at .94, was the spoken slowpoke at 5.18 syllables per second. Spanish, with a low-density .63, ripped along at a syllable-per-second velocity of 7.82. The true speed demon of the group, however, was Japanese, which edged past Spanish at 7.84, thanks to its low density of .49. Despite those differences, at the end of, say, a minute of speech, all of the languages would have conveyed more or less identical amounts of information.” via TIME

It was my brother’s birthday yesterday. Rather than offer a lot of obligatory “Happy birthdays,” my siblings and I did this: Continue reading…

Excepting more embarrassing personal stuff, here are the changes I hope to make next year:

- I’m gonna speak softly to my kids. I’m loud. With my choice of words and opinions as much as my volume. Children don’t need that extra emotion as they’re figuring out the world. Often times I bark at my kids when they make a mistake or disobey. On a whim recently, I tried something different. Instead of scolding my three year old with a mean face and verbal outburst, I kneeled down, leveled my eyes with hers, softly expressed my disappointment, and encouraged her to change. She lovingly accepted and immediately improved her behavior. After overhearing the exchange, her older sister said, “Dad, I like when you talk to us like that. I feel a warm spirit in the room when you do that.” Then this happened. Then I resolved to speak kindly when disciplining my children from that day forward. Continue reading…

My wife and I went to a screening of Unfortunate Brothers last night. It’s an affecting documentary by Dodge Billingsley about the political, economic, and cultural divide of North and South Korea.

My wife and I went to a screening of Unfortunate Brothers last night. It’s an affecting documentary by Dodge Billingsley about the political, economic, and cultural divide of North and South Korea.

The film is touching, insightful, and kept me engaged for 55 minutes. It also made me sympathize with the plight of North Koreans.

The only problem: The movie was screened to a group of eggheads at BYU, my alma mater, and all the academic and naive student types that congregate there. And not just any kind of academics—the “international relations” kind that like to talk political theory, solve other country’s problems from afar, and use big words to make themselves feel like they’re contributing to society.

For example: After the screening, an expert panel of three pleasant fellows including the filmmaker fielded questions from about 80-100 attendees. The second “question” came from an assumed student that liked to hear himself talk. He talked about how the movie “moved” him. In between lengthy pontifications, he said, “I guess my question is” three times. He talked a lot. He was the opposite of concise. Continue reading…

I’m amazed by the phrase “agree to disagree.”

It’s a lazy expression. It’s contradictory. Yet it works. But only because it’s a cliche.

If it weren’t a common expression, the receiver would dismiss it as being stupid and probably stay on the offensive. (See Mister English Teacher: Who said cliches don’t have a place in language. Writing never, but speech, yes.)

In my own life, I’ve agreed to disagree (or agreed to differ) on numerous occasions. It’s funny how it always seems to work in terminating thought. It’s like the white flag of verbal disagreement. “Oh, I give up.”

More impressive, however, is that “agreeing to disagree” instantly facilitates civility and tolerance. Who would of thought that a dumb cliche could be capable of such a thing?

Fascinating.

OMG, when did we start talking like txt msgs?

One possibility, Kiesling proposes, is that some of these acronyms actually become a whole new thought, expressing something different than the words that form them. For example: “You wouldn’t say, `OMG, that person just jumped off a cliff,'” he explains. “But you’d say, `OMG, do you see those red pants that person is wearing?'”

I went to lunch today with an old business school buddy. We always have a good time making fun of brainless ideas while trying to make a honest buck. Today, we ridiculed some of the following business cliches, which are beyond stale and should never be used; otherwise you’ll sound like everyone else and influence few:

I went to lunch today with an old business school buddy. We always have a good time making fun of brainless ideas while trying to make a honest buck. Today, we ridiculed some of the following business cliches, which are beyond stale and should never be used; otherwise you’ll sound like everyone else and influence few:

Continue reading…

I think rhetorical questions can be a persuasive and colorful form of language, but only when left unanswered.

I’m not sure how or when it started, but answering your own insincere rhetorical question seems to be increasingly popular these days, especially among public relation and business folk. Here’s how they do it: “Am I happy about [insert any controversial issue here]? No. But… [insert any justification here].” Worse still, rhetorical answer lovers will often string together three negative questions, followed by a mega justification. Dumb.

Good communication is concise and precise, replete with active voice and direct sentences. In other words, I don’t like when people answer their own rhetorical questions.

Associated Press

Slate has an enlightening story on how failure became “fail” in popular, always-abbreviated, internet speak. Not only is “fail” a hilariously fitting disciption for utter incompetence, it seems the nerb (or voun) is here to stay, just like other verb to noun combos such as “to bike” and “bike,” and “to lock” and “lock”. Definitly not fail.

According to Dictionary.com, “diffident” is an adjective describing someone who is:

1. lacking confidence in one’s own ability, worth, or fitness.

2. restrained or reserved in manner, conduct, etc.

Good word. Will have to use it more.

“Not all 🙂 as informal writing creeps into teen assignments,” reads a clever AP headline. Here’s an excerpt:

It’s nothing to LOL about: Despite best efforts to keep school writing assignments formal, two-thirds of teens admit in a survey that emoticons and other informal styles have crept in… “It’s a teachable moment,” said Amanda Lenhart, senior research specialist at Pew. “If you find that in a child’s or student’s writing, that’s an opportunity to address the differences between formal and informal writing. They learn to make the distinction … just as they learn not to use slang terms in formal writing.”

First of all, I love how avant guard the Associated Press was in using that playful headline in a formal news report. Secondly, I whole heartily agree that there’s a time and a place for informality. That goes for speech as well.

I always get a good chuckle hearing people say something other than “Internet.” Having personally celebrated over 50 years* online, these are my favorite alternatives:

- Cyberspace. A fancy word presumably created by school teachers to give the simple sounding Internet a sense of exploration. Use sparingly for comedic delivery.

- Information Super Highway. School teachers that took the glitzy sounding Cyberspace to the next level. Never use in serious situations. Continue reading…

While on a recent cruise, I played on-board tennis with a Belgian girl and a married couple from South African. It was decided that I would play doubles with the Belgian, upon which she asked, “Which side would you like to play?”

I answered her question with a question: “Which side would you like play?”

“No, I’m asking you a question,” she authoritatively said in a thick European accent.

“Oh, right — I guess you did. I’ll take the right side,” I responded.

I couldn’t help but chuckle at the language confrontation. In trying to be overly courteous, as many Americans do, I complicated what should have been a simple exchange. The take-away: forced modesty should always be avoided.

I saw Me and My Girl last night — a play that takes place in 1920s England. The performance was entertaining (a bit stale at times), but I really enjoyed the English… which got me thinking of the funniest British words. They are:

I saw Me and My Girl last night — a play that takes place in 1920s England. The performance was entertaining (a bit stale at times), but I really enjoyed the English… which got me thinking of the funniest British words. They are:

- Bollocks. Figurative meaning: nonsense. Technical meaning: testicles. Codswallop is a less-descriptive substitute.

- Trousers. These are what Americans call “pants.” We understand the former term, but you’d get ridiculed for using it.

- Blimey. Is there a cooler way to say “wow” or “holy crap?” I think not.

- Salad-dodger. Quite possibly the funniest word I’ve ever heard for a fat, obese, or overweight person. Continue reading…

My wife and I went to a screening of

My wife and I went to a screening of  I went to lunch today with an old business school buddy. We always have a good time making fun of brainless ideas while trying to make a honest buck. Today, we ridiculed some of the following business cliches, which are beyond stale and should never be used; otherwise you’ll sound like everyone else and influence few:

I went to lunch today with an old business school buddy. We always have a good time making fun of brainless ideas while trying to make a honest buck. Today, we ridiculed some of the following business cliches, which are beyond stale and should never be used; otherwise you’ll sound like everyone else and influence few:

I saw

I saw