Published works: If the Internet never happened, how might we live today?

courtesy reddit

An edited version of this story first appeared on April 5, 2016 in The Atlantic

Not long ago, I stumbled on a list of the best sci-fi novels according to the Internet (i.e. the highly entertaining computer geeks on Reddit). As someone who reads for pleasure as much as job security, I decided to finish as many of these and others that I could handle.

After completing over a dozen—not to mention many more in film adaptations—the following occurred to me: every single one of these acclaimed, futuristic stories—at least the many I was exposed to—completely missed the existence and impact of the Internet. Everything from published media and daily communication, to realizing sight unseen romance and access to global markets.

Why?

“A lot of science fiction was primarily focused on moving people and things around in exciting ways,” says technology commentator Clive Thompson. “These forward-thinkers were using flashy visuals to hook their readers, while understandably overlooking non-sexy things such as inaudible conversations.”

Which is largely what the Internet facilitates. Like electricity, it’s really just an everyday utility now. And utility talk is not plot. It’s boring.

Perhaps the biggest reason then? “The Internet was too big of an idea for any single author or person to dream up,” explains Michael Calore, senior editor at Wired Magazine. “It’s been a collective and abstract shift; an ongoing reflection of us as social creatures.”

Looking back

Established in the ‘60s by the Department of Defense, expanded in the ‘70s and ‘80s by American universities, and popularized in the ‘90s by Tim Berners-Lee and America Online, the Internet today “is just a world passing around notes in a classroom,” according to comedian Jon Stewart.

So how might we live without the world’s largest note exchange?

The easiest starting point is to examine life before 1990. Landline telephones. Prevalent handwriting. Everyday typewriting. Facsimile machines. Long distance calls. Nineteen inch televisions. 8-bit graphics. Nine to five work schedules. VHS rental stores. Record stores. Book stores. Limited kids’ programming (i.e. after school and on Saturday mornings only). Scarce pornography. Abundant garage sales. A more isolated society with fewer voices.

Zero apps for that.

But that historical reality doesn’t really answer the question because in an alternate history, we wouldn’t have known what we were missing. “The internet has so permeated our lives that its influence is becoming impossible to see,” says longtime Internet philosopher Clay Shirky. “Imagining ‘today, minus the net’ is as content-free an exercise as imagining London in the 1840s with no steam power, New York in the 1930s with no elevators, or L.A. in the 1970s with no cars. After a while, the trellis so shapes the vine that you can’t separate the two.”

For enlightenment’s sake, let’s try. Take the life of Brian Lam, for example. After helping Gizmodo become the most popular gadget publication as its then editor, Lam walked away in 2011 and moved to Hawaii to start a less ephemeral publication, The Wirecutter.

“As a business owner, I couldn’t do what I do today without the Internet,” Lam says. “My team and I would be forced to live in a big market, probably New York. Consequently, I’d have less access to the outdoors, no access to the global talent I currently employ, and a narrower perspective.”

On the flipside, he says, some wage earners aren’t so lucky. Rather than use the Internet to free their workers, some employers might exploit them with it; demanding more from them without paying overtime. (See also: “Powerful tools are always dangerous.”)

In addition to devouring the lines between work and home life, the Internet has dramatically challenged our patience. “Without it, we wouldn’t expect instant gratification as often as we do,” notes Calore. “Not just the ability to get an online answer immediately or same-day delivery. Because of the Internet, the anticipation of waiting for things is largely gone.”

Looking forward

When Steve Case co-founded America Online 30 years ago, just 3% of America was online (mostly academics). Before the web was invented, these early adopters spent less than an hour a week on “cyberspace” (mostly email). At the peak of his company’s reign in 2000, half of America used Aol to get online.

Today, 92% of America is online, albeit through varying providers and with daily usage as high as 8–12 hours in some cases. Although Case is no longer in the connectivity business, the goal remains the same.

“We designed it to connect people with shared interests and ideas; to produce more durable offline relationships,” he says. “We tried to level the playing field by reducing the cost to communicate and increasing efficiencies so that more voices and greater perspective could be found.”

After revolutionizing information, entertainment, and, of course, passing classroom notes around, Case expects much greater things from the next wave of the Internet. “Most of the things that really matter haven’t changed—healthcare (which represents one sixth of our economy), education, food, and government” are all going to the helpdesk, he argues in his upcoming book, The Third Wave.

Improvements to healthcare, government, and pencil and paper-free education I can wrap my head around. But food? “You’ll still eat a banana,” Case admits, “but the speed at which it makes it to your table from the farm will increase.” Better nutrition through smarter sourcing.

What about improvements to discussion though? Everyone agrees comments are a hiveminded mess now, not to mention worse than they were 10 years ago before social media fragmented single-page conversations into a million, tiny pieces onto groupthink walls.

“It’s a problem,” Thompson confesses thoughtfully. “I’d like to see the return of centralized commenting.” But we won’t be stuck with this for five years, he predicts. “I understand developers who are already trying to fix this.”

They’ve got their work cut out. Next to streaming video, siloed social media is the Internet’s favorite pastime. The garden that was once so open is being increasingly segregated.

Living in a heads-up world

Having the Internet in our pocket has changed who we are, argues Sherry Turkle, an MIT professor who’s researched online behavior for more than 30 years. She points to a recent University of Michigan study that found a 40% decline in empathy among college students, with most of the dropoff taking place as the illusion of social media obviated the need for face-to-face and real-time communication.

“Across generations, technology is implicated in this assault on empathy,” Turkle recently wrote for the New York Times. Since many of us are connected for a third of our day or more, “We have found ways around conversation that is open-ended and spontaneous, in which we play with ideas and allow ourselves to be fully present and vulnerable.”

Calore seconds Turkle’s concern. “The internet isn’t very good at building empathy,” he tells me sharply. Then he goes all Good Will Hunting on me, adding that while the Internet is a remarkable tool for accelerating knowledge, casual relationships, and simulated experiences, it can never replace the physiologically experience of being somewhere with another.

“You can get some way on the Internet, but actually being there gives you a profound understanding,” he says. “In that way, the Internet reduces our social life. Admittedly, it’s not turning us into inhumane monsters, but it complicates our ability to intimately connect with each other.”

Lam has mixed feelings. “I wouldn’t be happy without the Internet, but it does make me miserable at times.” Even with disciplined use of it, he cautions, the Internet can quickly turn from convenient tool that makes life amazing into something that traps us.

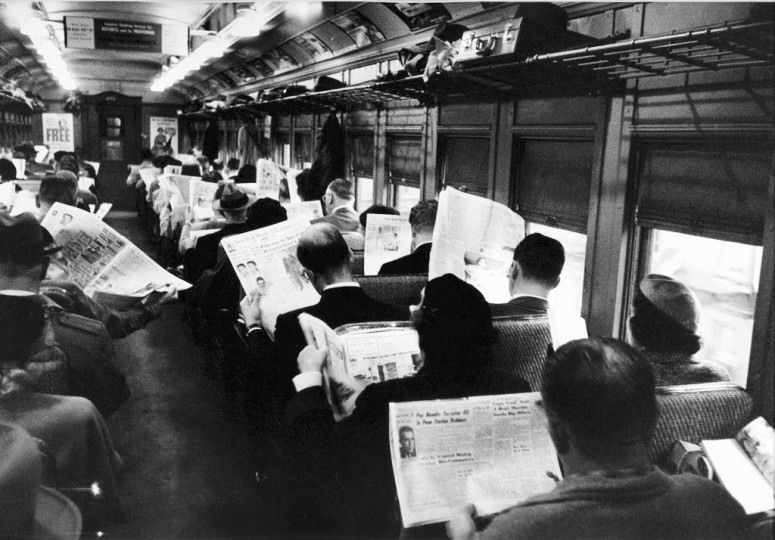

But antisocial, heads-down behavior existed well before the intertubes existed, as this recent viral photo (pictured) so effectively reminds us. Not only that, but Thompson believes the ills of compulsive Internet use have been greatly exaggerated. “I’m not convinced it’s the epidemic it’s made out to be,” he says.

“It’s called frequency illusion. In this case, seemingly obsessive phone use understably annoys us, so we notice more than it actually occurs… without seeing the 90–97% of people that aren’t head-down on their phones.”

Research supports this, Thompson says, citing surveys from Rutgers and others — in addition to his own personal attempts at corroborating the evidence — which puts random public phone use in the not-so-scary range of just 3-10%. “Truth is, we had this same argument with the telephone,” he reminds me, “That it would reduce total social encounters when, in fact, it facilitated more of them.”

Shirky believes any attempt to separate the Internet from everyday life is futile, while also calling out three sci-fi authors that did predict the Internet. “Just as it took Isaac Asimov, Vernor Vinge, and William Gibson to imagine the importance of ubiquitous, free communications, the only credible post-internet visions are all tied to civilizational collapse: zombie apocalypses, global pandemics, nuclear catastrophes.

“The hidden message in all of those scenarios is that if the only way to convincingly imagine a world without an internet is to imagine a world without civilization, then to a first approximation, the internet has become our civilization.”

For his part, Case believes as most do that the Internet has been an overall net positive for billions of people, especially since it was never intended to replace analog life. But he and his contemporaries are still trying to answer the same question that he posed 30 years ago to his team at Aol.

“When expanding the Internet, how do we augment the positives while minimizing the negatives?”

About the author: Blake Snow writes epic stories for fancy publications and believes people are inherently good. His work has appeared in NBC, CNN, Fox News, and Wired Magazine among others. If you made it this far, thank you for reading.