This is what old people talk about over lunch: how degenerate youth no longer use capitals and punctuation when writing. At least that’s what I did over lunch today with a few middle aged friends.

This is what old people talk about over lunch: how degenerate youth no longer use capitals and punctuation when writing. At least that’s what I did over lunch today with a few middle aged friends.

This is especially important to me because I’m in the business of selling clear writing. Having done so for many years, this much I know: the clearer you write, the better chance you have of avoiding confusion and getting what you want.

A few years ago, a recent college graduate and aspiring writer emailed me to ask for help in getting a job. He used no capitals, punctuation, paragraphs—let alone line breaks. It was just one huge blob of text. Continue reading…

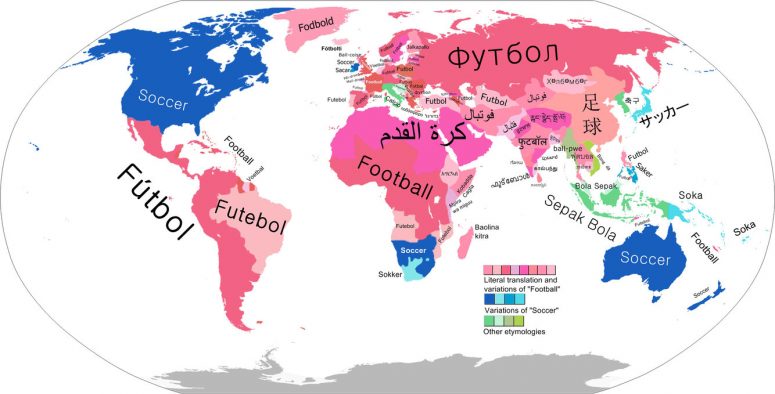

Courtesy Reddit

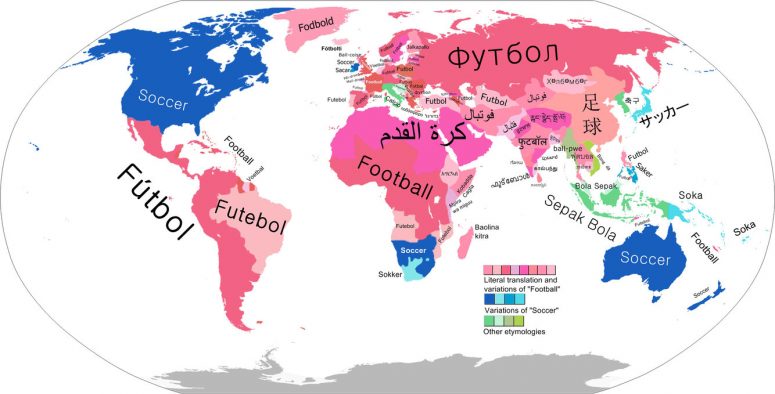

In fact, Irish, South Africans, Canadians, Australians, Kiwis, and even four-time World Cup champions Italy call the sport something other than “football.” In addition to America, the first five say “soccer,” while the latter call it “kick ball.”

As for how “soccer” got it’s name, the English actually invented it, according to the U.S. Embassy in London:

“Soccer’s etymology is not American but British. It comes from an abbreviation for Association Football, the official name of the sport. For obvious reasons, English newspapers in the 1880s couldn’t use the first three letters of Association as an abbreviation, so they took the next syllable, S-O-C. With the British penchant for adding ‘-er’ at the end of words—punter, footballer, copper, and rugger—the word ‘soccer’ was born, over a hundred years ago, in England, the home of soccer. Americans adopted it and kept using it because we have our own indigenous sport called football.”

There you have it. Don’t like the name “soccer,” blame the British.

Six months after I started blogging in 2005, I got my first check for writing. I’ve learned a lot since then. But many professional stories, outlets, and years later, I still didn’t know how to distinguish an em dash (the really long hyphen) from parentheses.

That is until this week. Turns out, em dashes are reserved for brief interuptions that are unrelated to the preceding clause, whereas parentheses are primarly reserved for clarification of the preceding clause, writes Sarah Stanley, who strikes again! For example:

- Johnny asked me—with a straight face, I might add—if he could borrow the car for the weekend.

- Anyone can edit Wikipedia (not that there’s anything wrong with that).

Continue reading…

MGM

I watched Nicholas Nickleby over the holidays with my soulmate.

It’s worth watching, at least according to this romantic. Charlie Hunnam’s performance was uneven—brilliant when confronting his uncle, not so much when mourning the death of his friend. But it was obvious to me after watching it: Charles Dickens is a masterful storyteller. He’s proved it many times over. As have his contemporaries, including Jane Austen.

Upon finishing the movie and while channeling the most formal English I could muster, I commented to my wife, “We gotta go to England! The source of such great storytelling deserves to be honored with our presence.”

Plus, I’m a sucker for Ferris wheels, and I hear London has a rather considerable one.

See also

My wife and I went to a screening of Unfortunate Brothers last night. It’s an affecting documentary by Dodge Billingsley about the political, economic, and cultural divide of North and South Korea.

My wife and I went to a screening of Unfortunate Brothers last night. It’s an affecting documentary by Dodge Billingsley about the political, economic, and cultural divide of North and South Korea.

The film is touching, insightful, and kept me engaged for 55 minutes. It also made me sympathize with the plight of North Koreans.

The only problem: The movie was screened to a group of eggheads at BYU, my alma mater, and all the academic and naive student types that congregate there. And not just any kind of academics—the “international relations” kind that like to talk political theory, solve other country’s problems from afar, and use big words to make themselves feel like they’re contributing to society.

For example: After the screening, an expert panel of three pleasant fellows including the filmmaker fielded questions from about 80-100 attendees. The second “question” came from an assumed student that liked to hear himself talk. He talked about how the movie “moved” him. In between lengthy pontifications, he said, “I guess my question is” three times. He talked a lot. He was the opposite of concise. Continue reading…

Describing someone’s current state as “emotional” is about as helpful as saying someone is human. Let me explain.

Whenever someone wins something on camera, they often cry as a result and describe their state of being as “emotional.” Athletes do this. Celebrities do this. People that feel blessed do this.

But it’s a vague adjective in the temporary sense of the verb “to be” (i.e. estar in Latin). Of course these people are emotional. The audience can obviously see that. What these victors and fortunate people on camera should really be saying is that they are overjoyed, elated, incredibly happy, deeply thankful; anything to more accurately describe what they’re feeling rather than the cliche, diluted, and catch-all “emotional.”

That said, emotional succeeds as a permanent descriptor of the verb “to be” (ser for any Spanish or Portuguese readers out there).

For example, I’m an emotional guy (right Lindsey!?), which means I cry more than most men, I’m enthusiastic, I’m impulsive, I’m responsive, I’m romantic, and I feel like a jerk after making even minor mistakes.

So next time you’re feeling an intense feeling, try to describe what it is you’re actually feeling. You’ll make a better impression, learn more about yourself, and enjoy the moment even more.

If there’s one writing habit I simply adore, it’s seeing a writer use “back in” when referencing previous years or months.

If there’s one writing habit I simply adore, it’s seeing a writer use “back in” when referencing previous years or months.

For example: “Back in 1845…” or “Back in December.” In such instances, the leading “back in” solidifies my otherwise horrible sense of time. Without that “back in,” I’d be completely lost.

Just today, reading a cryptic “In 1997” left me utterly confused. Since I have no concept of past, present, or future tense verb usage, I wasn’t 100% certain the writer was referencing history.

Worse is when a concise writer references a previous month without the oh-so-enlightening “back in.” After all, it’s not like the reader can assume you’re talking about a previous month, especially since you didn’t also reference a year. Case in point: Is “In July” talking about past July or next July? It’s ambiguous. I mean, next we’ll be asking writers to say “next” when referencing the future. It’s unheard of.

So remember writers: Never assume a reader understands chronology. As such, always say “back in” when referring to the past. It’s not wordy or presumptuous at all.

Ask any American what they think of the English Royal Family, and even the most liberal voter will tell you it’s a waste of taxpayer money (since the family is powerless). Whether or not that’s the case, the level of U.S. government waste far exceeds that of the Royal Family.

For example, the British Royal Family costs the UK taxpayer $64 million per year, excluding travel and security. That’s about a dollar per person. The travel budget for the U.S. president alone is several times that.

The Homeland Security Agency, which like the Royal Monarchy, is suppose to make citizens feel all warm and fuzzy inside, costs the U.S. taxpayer $55 billion a year! What do we get in return? Mandatory shoe removal at airports, 15,000 wasted jobs, a failed alert system, and more exciting deployments for the Armed Forces (you know, the people who should be managing homeland security in the first place, like they honorably and successfully did prior to HSA’s creation).

And that’s just one of hundreds of wasteful agencies.

So the next time you get all high and mighty on Team America for not wasting money on an opulent spokesfamily, ask yourself what U.S. department was watched by more than 2.5 billion people in a mostly favorable light this morning?

I’m amazed by the phrase “agree to disagree.”

It’s a lazy expression. It’s contradictory. Yet it works. But only because it’s a cliche.

If it weren’t a common expression, the receiver would dismiss it as being stupid and probably stay on the offensive. (See Mister English Teacher: Who said cliches don’t have a place in language. Writing never, but speech, yes.)

In my own life, I’ve agreed to disagree (or agreed to differ) on numerous occasions. It’s funny how it always seems to work in terminating thought. It’s like the white flag of verbal disagreement. “Oh, I give up.”

More impressive, however, is that “agreeing to disagree” instantly facilitates civility and tolerance. Who would of thought that a dumb cliche could be capable of such a thing?

Says The Hot Word, my new favorite blog:

Says The Hot Word, my new favorite blog:

Many people believe Moon Unit Zappa and her 1982 single Valley Girl are responsible for popularizing this usage of “like” precisely at the moment Ms. Zappa sang, “It’s like, barf me out.” In reality, the slang use of the word “like” has been a part of popular culture dating as far back as 1928 and a cartoon in the “New Yorker” that depicts two woman discussing a man’s workspace with a text that reads, “What’s he got – an awfice?” “No, he’s got like a loft.” The word pops up again in 1962’s A Clockwork Orange as the narrator proclaims, “I, like, didn’t say anything.”

Not only that, but the slang interjection was even found in a novel circa 1886. Tubular!

Fascinating.

OMG, when did we start talking like txt msgs?

One possibility, Kiesling proposes, is that some of these acronyms actually become a whole new thought, expressing something different than the words that form them. For example: “You wouldn’t say, `OMG, that person just jumped off a cliff,'” he explains. “But you’d say, `OMG, do you see those red pants that person is wearing?'”

I went to lunch today with an old business school buddy. We always have a good time making fun of brainless ideas while trying to make a honest buck. Today, we ridiculed some of the following business cliches, which are beyond stale and should never be used; otherwise you’ll sound like everyone else and influence few:

I went to lunch today with an old business school buddy. We always have a good time making fun of brainless ideas while trying to make a honest buck. Today, we ridiculed some of the following business cliches, which are beyond stale and should never be used; otherwise you’ll sound like everyone else and influence few:

Continue reading…

You can blame England—the inventors of the game—not America for the word.

You can blame England—the inventors of the game—not America for the word.

As the U.S. Embassy in London explains, “Soccer’s etymology is not American but British. It comes from an abbreviation for Association Football, the official name of the sport. For obvious reasons, English newspapers in the 1880s couldn’t use the first three letters of Association as an abbreviation, so they took the next syllable, S-O-C. With the British penchant for adding ‘-er’ at the end of words—punter, footballer, copper, and rugger—the word ‘soccer’ was born, over a hundred years ago, in England, the home of soccer. Americans adopted it and kept using it because we have our own indigenous sport called football.”

Still don’t like the word soccer? You can file an official complaint with South Africa, Australia, Ireland, New Zealand, and a handful of others in addition to the U.S. who all refer to the sport as “soccer.”

See also

Nearing the end of Out of Africa (review forthcoming), I couldn’t help but notice how author Isak Dinesen used a lone “fortune” as opposed to the more popular “good fortune” when she wrote:

“Natives have such a feeling for, and faith in, fortune, that now, after one success, they may have begun to trust that all was going to be well, and that I was to stay on the farm.” p370

By using fortune alone, which itself implies success, Dinesen caused me, the reader, to pause and consider what she wrote, rather than skimming a cliche. You too can add more meaning in writing by avoiding clutter adjectives, which dilute the meaning of words. A good reminder.

I think rhetorical questions can be a persuasive and colorful form of language, but only when left unanswered.

I’m not sure how or when it started, but answering your own insincere rhetorical question seems to be increasingly popular these days, especially among public relation and business folk. Here’s how they do it: “Am I happy about [insert any controversial issue here]? No. But… [insert any justification here].” Worse still, rhetorical answer lovers will often string together three negative questions, followed by a mega justification. Dumb.

Good communication is concise and precise, replete with active voice and direct sentences. In other words, I don’t like when people answer their own rhetorical questions.

I finished reading Designing With Type over the weekend. In addition to providing useful tips, the resource book reminded me of type design techniques that I loath, which include (but are not limited to) the following:

- Double spacing after a period. I don’t care what your fifth-grade teacher taught you: never ever double space after a period. Thanks to improved technology, we don’t have to jerry-rig sentence spacing like typewriters did. One space suffices.

- Underlining. Another antiquity from the typewriter days, underlining is a manual technique copywriters used to emphasis a word or sentence by returning to a previously typed section and underlining it with the underscore character (_). There’s no longer any use for it, even in web links (because we have color links). Use italics, a quieter, more readable alternative to highlighting. But use them sparingly, please — like once or twice max for any given document. Continue reading…

Associated Press

Slate has an enlightening story on how failure became “fail” in popular, always-abbreviated, internet speak. Not only is “fail” a hilariously fitting disciption for utter incompetence, it seems the nerb (or voun) is here to stay, just like other verb to noun combos such as “to bike” and “bike,” and “to lock” and “lock”. Definitly not fail.

According to Dictionary.com, “diffident” is an adjective describing someone who is:

1. lacking confidence in one’s own ability, worth, or fitness.

2. restrained or reserved in manner, conduct, etc.

Good word. Will have to use it more.

“Not all 🙂 as informal writing creeps into teen assignments,” reads a clever AP headline. Here’s an excerpt:

It’s nothing to LOL about: Despite best efforts to keep school writing assignments formal, two-thirds of teens admit in a survey that emoticons and other informal styles have crept in… “It’s a teachable moment,” said Amanda Lenhart, senior research specialist at Pew. “If you find that in a child’s or student’s writing, that’s an opportunity to address the differences between formal and informal writing. They learn to make the distinction … just as they learn not to use slang terms in formal writing.”

First of all, I love how avant guard the Associated Press was in using that playful headline in a formal news report. Secondly, I whole heartily agree that there’s a time and a place for informality. That goes for speech as well.

I always get a good chuckle hearing people say something other than “Internet.” Having personally celebrated over 50 years* online, these are my favorite alternatives:

- Cyberspace. A fancy word presumably created by school teachers to give the simple sounding Internet a sense of exploration. Use sparingly for comedic delivery.

- Information Super Highway. School teachers that took the glitzy sounding Cyberspace to the next level. Never use in serious situations. Continue reading…

While on a recent cruise, I played on-board tennis with a Belgian girl and a married couple from South African. It was decided that I would play doubles with the Belgian, upon which she asked, “Which side would you like to play?”

I answered her question with a question: “Which side would you like play?”

“No, I’m asking you a question,” she authoritatively said in a thick European accent.

“Oh, right — I guess you did. I’ll take the right side,” I responded.

I couldn’t help but chuckle at the language confrontation. In trying to be overly courteous, as many Americans do, I complicated what should have been a simple exchange. The take-away: forced modesty should always be avoided.

I saw Me and My Girl last night — a play that takes place in 1920s England. The performance was entertaining (a bit stale at times), but I really enjoyed the English… which got me thinking of the funniest British words. They are:

I saw Me and My Girl last night — a play that takes place in 1920s England. The performance was entertaining (a bit stale at times), but I really enjoyed the English… which got me thinking of the funniest British words. They are:

- Bollocks. Figurative meaning: nonsense. Technical meaning: testicles. Codswallop is a less-descriptive substitute.

- Trousers. These are what Americans call “pants.” We understand the former term, but you’d get ridiculed for using it.

- Blimey. Is there a cooler way to say “wow” or “holy crap?” I think not.

- Salad-dodger. Quite possibly the funniest word I’ve ever heard for a fat, obese, or overweight person. Continue reading…

Everyone and their dog says “mischEEvious” not “mIschievous.” So should the spelling be changed to reflect widespread American use, or is that English heresy?

Connect Magazine has a fairly new ad campaign aimed at soliciting user-generated feedback from its readers. The campaign shows close-ups of several individuals (some prominent) with the quoted text, “I’m Editor-in-Chief,” suggesting that anyone can make recommendations for improvement. That’s a good thing. So it is in this public forum and with the utmost respect that I offer the following two suggestions after reading the first article from the magazine’s January issue (Nota bene: The online version only contains half of the print formatting problems I’ll discuss below):

-

Reference yourself as a proper noun. As you’ll see on both the online and print versions of Connect Magazine, the publication always references itself in-paragraph as “connect” sans capitalizing the “c” despite their being a proper noun. The reason — I suspect — is because the publication uses all lowercase letters in their logotype like several other companies do including my own. But the war waged against uppercase proper nouns in writing will never be won. Rather, the attempt in creating an exception to the rule is confusing to readers, and frankly, looks amateurish; like something a brash mom-and-pop shop would do shortly after creating their first company name. People don’t expect proper English on a creative logo, but they do expect it when reading copy. So ditch the lowercase “c” at the paragraph level if you want to mitigate confusion.

-

Quit changing the font type, its size, or its color in-paragraph. In paper form, Connect now uses a bright orange (its corporate color) when referencing itself or its URL in addition to snubbing conventional proper nouns. It also appears that they change the font type and its size a bit. This issue is largely more problematic that the first. It significantly reduces the readability by disrupting text continuity. The overall reading experience feels like that of driving your car over those annoying speed bumps in front of elementary schools. I’m betting the magazine did this in a vane attempt to combat the reader confusion cited above, which — if accurately assumed — would be ridiculous. And no, just because online articles can get away with colored hyperlinking doesn’t mean you can in print form. You’re a magazine not a website!

The above two suggestions are sure to increase the professionalism, usability, and most importantly, the readability of an already excellent publication. After all, Connect sells reading material for a living. They’d be wise not to alienate that experience for creativity’s sake or ambitious differentiation.

Disclosure: I write for Connect.

This is what old people talk about over lunch: how degenerate youth no longer use capitals and punctuation when writing. At least that’s what I did over lunch today with a few middle aged friends.

This is what old people talk about over lunch: how degenerate youth no longer use capitals and punctuation when writing. At least that’s what I did over lunch today with a few middle aged friends.

My wife and I went to a screening of

My wife and I went to a screening of  If there’s one writing habit I simply adore, it’s seeing a writer use “back in” when referencing previous years or months.

If there’s one writing habit I simply adore, it’s seeing a writer use “back in” when referencing previous years or months. Says

Says  I went to lunch today with an old business school buddy. We always have a good time making fun of brainless ideas while trying to make a honest buck. Today, we ridiculed some of the following business cliches, which are beyond stale and should never be used; otherwise you’ll sound like everyone else and influence few:

I went to lunch today with an old business school buddy. We always have a good time making fun of brainless ideas while trying to make a honest buck. Today, we ridiculed some of the following business cliches, which are beyond stale and should never be used; otherwise you’ll sound like everyone else and influence few: You can blame England—the inventors of the game—not America for the word.

You can blame England—the inventors of the game—not America for the word.

I saw

I saw