My friend’s daughter is an aspiring writer and recently interviewed me. This is what I told her:

1. Do you work for someone specifically or do you have an agent or have to find someone new to write for after you finish a project?

I own my own freelance writing business and spend around half my time asking people if I can write for them and the other half actually writing. I don’t have an agent.

2. What kind of writing is it?

Tech and travel writing for websites, newspapers, and Fortune 500 companies. I’ve also written a couple of books.

3. Do you enjoy it?

No. I LOVE it. Doesn’t feel like a job. More like a calling really. I have no plans of retiring and intend on writing until I die, I like it so much. 😃 Continue reading…

I was recently asked if I write for myself or for others.

“Easy,” I exclaimed. “I write for myself.”

After 20 years of full-time writing, it means the world that my sentences, articles, and books have reached millions of people. Affirmation is my biggest love language.

But I never write for a single soul other than myself. I do this for two reasons. Continue reading…

Courtesy Shutterstock

To the nearly 5,000 of you who read my writing newsletter, thank you. I know many of you are working on writing projects both big and small. To that end, here are five simple things you can do right now to maximize the impact of your writing: Continue reading…

I was working with a client yesterday (Hi, Mike!) on some final edits of a publication-ready story. I really liked how the article turned out. But just as it was about to leave the door, Mike wanted to add the word “business” in front of “performance” in an early sentence, as in “business performance,” instead of just “performance.” I disagreed, because “companies” were the subject of the sentence, so the extra word wasn’t needed. That’s because most (if not all) readers will rightfully assume for-profit companies aren’t in the business of “philanthropic” performance or some other kind of performance. It’s all business all the time for them.

This isn’t the first time I’ve encountered keyword stuffing while working with clients. It certainly won’t be the last. While “search engine optimization” has made keyword stuffing worse, I believe there is another root cause of word stuffing. Executives, marketers, and copyrighters spend the majority of their week working hard to build and promote their products and services. For them, it’s very important work. So they often view the exercise of writing as the greatest, latests, and sometimes last chance to tell their story. So rather than let their sentences breathe and sound human, they try to add every extra word they can to get the story straight. Continue reading…

WARNING: This is a sales call 😀

I normally don’t blog about anything but good free content. But here we are. It’s for good reason, though. Pinky swear.

Not long ago, a couple of clients (one tech, one consulting) independently approached me about a monthly retainer to help them with ongoing strategic and last-minute writing and editing projects as needed. That includes high-impact and pre-planned articles and editorial planning, but also unforeseen writing decisions and editing choices that need an outside pair of eyes to review and validate (that’s me!)

Both projects have turned out really well. So much so that I’ve decided to productize them as a “Editorial Lifeline.” Basically this new tool gives content, communications, and thought leadership executives on-call access to a seasoned writer of 18 years, who’s written for hundreds of fancy publications and Future 500 companies.

With the editorial lifeline product, subscribers get:

- A mix of regular short or long-form articles delivered monthly

- Strategic guidance for ongoing editorial decisions, big or small

- Rapid turnaround and response times to meet fast deadlines (aka “lifelines”)

- Fixed monthly/annual cost to stay under budget

- Full and updated access to my workbook: What 18 years of writing have taught me

Of course, I’m still committed to writing and advising on one-off custom articles or special editing projects. But I’m confident a lot more companies could benefit from a similar “writing lifeline.” If you or someone you know would like to learn more, please email me: inbox@blakesnow.com

Thanks for reading. Now back to our regularly scheduled programming…

Courtesy Warner Bros.

I’ve been writing full-time on a professional basis for almost two decades. In that time, I’ve written two books, hundreds or reports, and thousands of articles.

To publish that amount of work, I’ve also committed tens of thousands of mistakes. Maybe more. My last book alone contained thousands of errors after my editor bled all over it. On top of that, I was born with bad diction, and am subjected to nasty hate mail after some of my mistakes.

Why am I telling you this?

Because in both life and writing, mistakes are an everyday thing. In fact, the latter happen every minute. That’s because language and communication are incredibly complex, even for professionals like me who get paid to write fewer mistakes than you do. The sooner you accept, if not embrace, mistakes, the better writer you’ll be. Continue reading…

When it comes to great writing, practice will only get you half of the way. To really gain an understanding of how language currently works (and how it fails), we must read often.

That’s admittedly hard for many people. One in four of you reading this didn’t read a single book last year, according to Pew Research. And the 75% who did only reported reading “at least” one book in the last 12 months, so it’s unclear what the average number of read books per year is.

In my own life, I have friends that read over 100 books a year. And I have friends that read no books. I like both kinds, but I know the former are better writers (and often communicators) than the latter. Personally, I read a dozen books per year, in addition to a similar number of long-form articles each week (via Longreads and Digg).

Wherever you are, sometimes we forget the impact that regular reading has on effective writing. This is your reminder. As we head into the holidays and new year, I challenge each of you to read more often. If you need a recommendation, read my recently reviewed books, my own two books, and/or subscribe to the above. Not only will this make you smarter, it will make you a better writer.

Need help writing anything next year? If so, I know a really good guy. Thanks for reading.

This is what I emailed to him earlier this year:

This is what I emailed to him earlier this year:

Hi, Clark.

I think I found you!

With the help of an old friend who remembered your last name this week, some helpful secretaries at BYU who identified your first name, and some Google sleuthing, I think you’re the professor that unknowingly changed my life.

Let me explain. I majored in business because I didn’t know what I wanted to do. I had a couple of cantankerous English professors that mistakenly made me believe I didn’t like writing. That all changed when I met you.

The specifics are foggy, but I clearly remember you giving me the greenlight to write about my passions, anything I wanted really, which was all it took to flip the switch on falling in love with writing sentences for a living.

Shortly after taking your MCOM class, I started blogging everyday. I wrote every day. And I have done so ever since as a freelance writer and journalist. It took me a couple of years after graduating in 2004 to go full-time, but I soon did, and I’ve wanted to personally thank you ever since.

Thanks for altering my career course for the better. Writing feels more like a calling than a job. I’m so grateful for great teachers like yourself.

Better yet, I was thrilled to learn you live in Provo (I never left either). May I take you to lunch and hand-deliver my first two books sometime?

He answered yes, we’ve since gone to lunch, and plan on staying in touch. The world is an amazing place!

I didn’t want to become a writer until my second to last semester of college.

I was in business school at the time and wrongly assumed I didn’t like writing. That’s because I took a couple of freshman English prerequisites that were taught by crotchety old professors who were more concerned with grammar and punctuation than writing with substance. So I assumed English and writing was the study of syntax, not creative or effective communication.

That all changed when I met Clark Hammond, my professor of the mandatory business writing class I had put off until my final year of school. The specifics are foggy, but I clearly remember him giving me the green light to write about whatever subject interested me most that semester. At the time that was sports and video games. So that’s what I wrote about, and it was a blast!

Because I was writing about something that interested me, I finally made it a point to learn the proper “syntax” so my message could reach the widest possible audience. In that way, I still learned what my earlier English professors wanted to, I just did it with my heart this time because the substance actually mattered to me.

I’ve written almost every day of my life ever since. I’ve covered dozens of topics and only turned down a handful that just didn’t excite or interest me. Obviously we’re all forced to write about things we aren’t passionate about. But as long as you write about what you know for sure, what you believe in most, or the point of view that matters to you most, honesty will always come through in your writing.

You want this because readers are starved for honesty. They get bombarded with so much fakery, so much “forced” writing.

So they next time you put fingers to keyboards, try to write from the heart. And if you’re heart’s not fully in it, at least try to write from a perspective that matters most to you. Your writing, influence, and readership will be better for it.

See also: Bestselling author Blake Snow enters the Provo music scene

I was recently asked to ghostwrite an article about autism in the workplace. The draft I was given used “different” about half a dozen times to describe autistic people. As a writer, that’s five times too many; maybe even six too many, since “different” is a boring, catch-all adjective that’s too vague to hold any real meaning.

Like I always do when wordsmithing, I started replacing redundant adjectives with new synonyms to keep things moving. This is because readers quickly get bored, and my job is to keep them reading until the final punctuation.

As I rewrote and constructed new sentences, I used several adjectives and descriptions that were later rejected and/or deemed too sensitive at best, derogatory at worst. The words I chose didn’t imply “of little worth,” which is the definition of derogation. Nevertheless, all but “different” and “neurologically diverse” were rejected.

While I still enjoy incredible first amendment freedoms as a writer, I will say the craft has gotten slightly more sensitive in recent years. There’s even a double standard sometimes. For example, it’s deemed appropriate to refer to non-autistic people as “typical” but frowned upon to refer to autistic people as “atypical.”

Although 95% of my editors are fantastic, it’s discouraging when someone rejects my honest attempt to keep writing fresh with accurate and stimulating adjectives. It rarely happens, but some editors favor politically correct terms over clarity and diverse writing. Ultimately that’s a disservice to the subjects themselves—in this case a lovable, unpredictable, and soft-spoken subsect of humanity.

Moral of the story: When descriptive words are limited, I believe readers and subjects both lose. As I’ve said before, it’s better to offend one reader while reaching another instead of being ignored or overlooked by both. When describing reality, accuracy should always prevail.

Yes there are people that intentionally use derogative words to describe people they deem as inferior. But most of us aren’t like that. We should give the majority of people the benefit of the doubt. And we can always follow up if we’re unsure about someone’s intent.

You know—ask questions first, shoot last.

Courtesy Shutterstock

My advice: Spend almost as much time asking people if you can write for them as you do actually writing for them. In the early days, I spent upwards of half of my time asking editors if I can write for them. Most ignored me. Several rejected me. But a handful said yes. In other words, being a freelance writer requires a lot of hustle. That lessens the longer you’re in the game and the more “free” referral work you get as you build your reputation. But even now after years of bylines I have to hustle to ask people if I can write for them. Good luck!

My third book is in the works

An old friend recently asked what I’ve been up to lately. Here’s the full answer as of this year:

- Freelance writing. I’ve been writing full-time for 17 years now. Since the Great Recession of 2009, however, writing explanatory tech and business stories for Fortune 500 companies has made up the bulk of my work. That continues today, writing mostly for software and consulting companies, as well as some travel publications for fun.

- Non-profit speaking. With the generous support of my good friend Craig, I started speaking to local elementary school students as part of my non-profit. We have more events planned in the fall, and it feels good to extend the movement beyond the book. Our first campaign includes giving away cool t-shirts to encourage people to “Live Heads Up.”

- Starting my third book. It’s called Today I Crush All Negativity, and it attempts to explain when and how to be optimistic and when and how to be pessimistic, regardless if you believe the glass is “half empty” or “half full.” If all goes to plan, I hope to publish the by the end of the year. I can’t wait for you to read it. I’ve interviewed a few billionaires for their perspective and hope to do the same with some homeless folks, too.

- Releasing my second album. I am so proud of it, promise it doesn’t suck, and hope you listen to it if you haven’t already. If you listen to just one song, make it “Sorta Social.” To promote the album, I even started a band to tour locally in Utah.

- Middle-age parenting. My family is rapidly becoming an older, adolescent family instead of the early childhood one its been for a long time. I can just feel it—and it feels special. I can talk to my older kids like an adult, and the younger ones are very independent. As part of that, I’m trying to deepen my relationships with them to hopefully avoid any future “daddy issues.” I feel encouraged by that and am closer to my wife than ever before.

Wikimedia Commons

I don’t like academic writing. It’s mostly nonsense.

A few years ago, I said as much to my father who works in academia. Despite my insensitivity and lack of tact, I stand by my belief. Not because I’m incapable of admitting when I’m wrong. But because academic writing’s verbose language, impersonal tone, and dispassionate delivery ultimately fail to engage readers.

In other words, “Academics are really good at writing books that only academics will read, but they’re not very good at making anyone outside of academia care,” says Jared Bauer, co-creator of Thug Notes, in an interview with Huffington Post. “Teaching isn’t easy, so I’m not trying to shame teachers for not trying more radical approaches to literature education,” he adds. “But at the very least, I hope (our) show makes teachers realize that a student won’t volunteer their attention. The teacher must seize it.”

As I debated with my father that day, for writing to succeed, it must capture the reader’s attention. If it doesn’t, the writing won’t get shared, influence can’t happen, and the opportunity to learn is squandered, even among scholars. There’s no point to that kind of writing other than to serve as a reminder of how not to write. Continue reading…

I recently finished When Breath Becomes Air by Paul Kalanithi. I was utterly moved by this powerful account of Kalanithi’s own life as a neurosurgeon, the most demanding physician in the world, and his own premature death in his mid thirties after contracting terminal cancer.

Not only was Kalanithi a paragon brain surgeon, though, he is an absolute poet on the meaning of life, the humanity of doctors, and making the most out of a terrible situation.

Rating: ★★★★★. These were my favorite passages: Continue reading…

Many years ago, I started a habit of writing regular gratitude letters to people who helped me, changed my perspective, or did something nice for me or my family. I even started writing letters to mentors from my past, authors of books that I admired, directors of movies I liked, musicians whose music I enjoyed.

To this day, I continue to write gratitude letters for the following reasons:

- Gratitude letters force us to feel grateful. That’s important because gratitude is the the number one way to increase our happiness, satisfaction, and fulfillment in life. It’s science, no joke.

- Gratitude letters spread joy. When people feel good about themselves, they are nicer to others and feel better about themselves. So if you want to make the world a better place for yourself and others, gratitude letters are an easy way to spread joy and increase kindness.

- Gratitude letters force you to write in different ways. I’ve written books, long-form articles, business reports, blogs, video scripts, and everything in between. But to this day, gratitude letters are some of the most challenging things for me to write, simply because they demand genuine thoughts and feelings. This makes me a better writer I believe.

Don’t know where to start? Consider this approach: “Close your eyes and think of someone who did something important for you that changed your life in a good direction but who you never properly thanked. It could be that you’re really grateful to a teacher who inspired your love of acting and who persuaded you to try for drama school when everyone else was dead set against it. Maybe you’d like to thank your boss or a colleague for helping you with a particularly tricky project at work. Or perhaps you choose to write a friend who helped you through a tough time… Describe specifically what they did and what influence it had on you. Let them know what you are doing now, and mention how you often remember what she did.”

Although I’d say a large portion of my gratitude letters go unanswered, that’s not why I write them. But it’s a sweet experience when I do get an answer. One famous writer wrote me eight months later saying he kept my email at the top of his inbox to remind himself that he was a good writer. Another director from Los Angeles wrote back and invited me to lunch the next time I was in town. The college professor that inspired me to become a writer replied saying he had no idea and that my email was a good reminder to him that we never know how our efforts touch the lives of others.

Moral of the story: people are amazing and writing gratitude letters is good for everyone.

Welcome to “Gutsy Writing” by Blake Snow—improve your writing in 5 minutes or less.

Several years ago, I was asked by a software director at one of the world’s largest technology companies to write a series of articles. He originally wanted me to explain the work his team was doing in a language that everyone understood. But as we talked further, he was having reservations about my breezy, informal writing style.

“Our audience doesn’t want to be talked down to,” he said, misinterpreting the point of clear writing, everyday speech, and simple words. “They take their work seriously, so the writing must use complex language and terminology.”

This was pure ego. Like some people, he needed big, technical words to feel good about the important work he was doing. And he was willing to sacrifice clarity, better readability, and greater reach to feel good about his highly technical job.

It was obvious I wasn’t a good fit, so I wished him luck in finding someone else. But my meetings with him underscored a cardinal rule that every novelist, journalist, and nonfiction writer adheres to:

Never use a long word where a short one will do.

If you can saying something with one syllable that can be said with two or more syllables, always use the shorter word. Your writing and readership will be better for it.

Need help writing this year? I know a really good guy. Thanks for reading.

Welcome to “Gutsy Writing” by Blake Snow—improve your writing in 5 minutes or less.

Not everyone can become a great writer, but a great writer can come from anywhere. The latter happens in one of two ways: they are naturally gifted like my wife, or they have to learn the hard way like I did.

For those like me, here are four certainties I’ve learned after 16 years of writing for fancy publications and Fortune 500 companies:

- Say what you mean. Never mask or muck up your message with buzz words, cliches, or technical gibberish in an effort to sound smart or more convincing. Readers value clarity over all else. So instead of adopting garbage speak like “transformation,” say “change” instead.

- Mean what you say. Be sincere in your writing. If you don’t believe what you’re saying, why should the reader? Secondly, use adjectives and superlatives sparingly. This builds credibility. And if you’re writing for a business (or ultimately trying to sell something), don’t hide the fact. Own it. Readers respect that.

- Compose conversations. Make your writing breezy. Use contractions 99% of the time. Keep your sentences short. Read them aloud to ensure you’re not gasping for air. Write like you would talk to a friend. Give it to them straight with informal language they cannot call your bluff on.

- Use spicy words. These little devils delight readers, give them pause, and force them to feel your sentences instead of skimming them. If you’re nervous or embarrassed to use a certain word, that’s probably the spice for you. Some of my favorites include bodacious, skedaddle, gusto, deafening, splendid, ballsy, terrific.

Be brave. You got this! 💪

Need help writing this year? If so, I know a really good guy. Thanks for reading.

Having written full-time for 16 years now, I’ve wanted to publish a free writing newsletter for sometime. This year I finally did it. SUBSCRIBE for free five-minute lessons every six weeks

Courtesy Lindsey Snow

I became a full-time writer 17 years ago.

While covering consumer technology and video games as a twenty-something blogger, I would regularly receive hate mail from fanboys (never girls) who disagreed with my reporting.

I even received several death threats on occasion. While I never took these threats seriously, it never feels good to have your life, family, or property threatened.

After leaving video games in the late aughts, the hate mail mostly stopped. But I still get upset emails sometimes.

A few years a go, a man berated me for an article I wrote for CNN that was missing a comma. “You have no credibility,” the anonymous man concluded. “If you can’t master simple grammar, you have no business writing.”

He’s not the only one who has questioned my continued mistakes, two books, and thousands of published articles. In fact, the hate mail I’ve received far outweighs the fan mail—which is not unlike sustained rejection in general. Continue reading…

My friend Tommaso and I after eating fresh pasta

Since much of the world is still partially closed or weird, I’ve taken a lot of comfort over the last year in the “simple things.” By that I mean everyday common things that are perpetually satisfying.

For example, here are 10 in particular that are paramount to me: Continue reading…

A good friend of mine recently launched a podcast that examines how authors get their books published. I spoke to him a few months ago, and here is my take on how I wrote and published my two books. Thanks for listening.

A friendly man named Michael recently asked me how to get published as a freelance writer. This is what I told him:

Most publications want pitches, not full-blown articles. This is for two reasons: 1) they care more about the idea first, and 2) they like to feel like they’re having an influence on its final form, one that’s specific to their publication.

While publications sometimes accept finished manuscripts, these are usually really big or unique or exclusive stories. I’ve only placed a few of those in my 16 year career as a writer, so I’d focus on really good pitches, and why you’re a good person to write it.

On top of that, I’d write everyday, if you’re not already. I’ve done this virtually every day through my blog, journal, and formal assignments. Since there’s no replacement for 10,000 hours of practice, that’s really the best way to improve your writing.

But doing the above only gets you half of the way. To get published, you often have to ask 100 editors if they’ll accept your pitch. Even I have to do this still. In short, placing articles is a grind. But I love the grind enough to stick with it until my article finally publishes.

TLDR; Placing articles is 50% good writing, 50% hustle (at least in my experience)

Watch this comical video to see what I mean. Not everyone talks like this, of course, but a lot of companies do.

For whatever reason (usually cultural ones), businesses like to speak in code to each other, and then they pay me to decode the nonsense into something actual humans can understand in written form.

It’s a confusing phenomenon, but I ain’t complaining. I love doing it.

See also: Why corporate speak is garbage language

If you enjoy the effort of doing something more than the result, you will be good at whatever you decide to do.

If you enjoy the effort of doing something more than the result, you will be good at whatever you decide to do.

In my case, when I spend days, weeks, months, or even years writing something, I love that process more than the minutes, hours, or days it takes me to read the result.

I’m not exaggerating to prove a point. It’s true. I love the act of writing more than the result (although the result is really nice icing on the cake that sustains me to the next result). Asking a lot of people if I can write for them is worth the rejection.

That’s how you know you can “win” at something—because you enjoy the mastery time, effort, and rejection required more than the average person.

In my case, I would write for free, I love it so much. Which is precisely how I started writing, for free, on this blog (and still do). Because I love writing so much, I’ve gotten good enough at it that people will pay me to write for them.

Which is a fulfillment of Joker’s absolutism: “If you’re good at something, never do it for free.”

I’ll disagree with him on the “never” aspect, since you sometimes have to work for free to keep learning and growing. But the point is hard work is valued.

So find work you love doing and the value will take care of itself.

An aspiring freelance writer recently emailed asking me how to increase her chances of placing articles with editors. She seemed eager to learn and willing to work, so this is what I told her:

- Keep your pitches (and requests in general) to a single paragraph. If you can’t sell a story or request for help in just a few sentences, you won’t be able to sell it in several paragraphs, which is annoying and disrespectful to an editor’s time. If they want more information, they’ll ask.

- Ask 100 editors if they’ll run your story. After most or all ignore you, ask them 3-4 times more. Often times it takes that much to get a favorable response, even after you get some good bylines under your belt. Usually I start by emailing my top 25 editors, and if no one bites, I’ll increase that number. But I didn’t place my first story with Wired Magazine until the 100th editor!

Lastly, I’d argue that most beginning writers struggle with wordiness. They like to hear themselves talk, and it shows in their bloated writing, which neither editors nor readers like. It sounds obvious, but to succeed as a freelance writer, you must be able to write in a way that appeals to a lot of other readers.

Think short sentences. Crystal clarity. Spicy words. Well-researched and genuine arguments. And in an increasingly distracted world, compelling writing requires more brevity than ever before.

Placing articles ain’t easy, but it’s totally worth it.

This is what old people talk about over lunch: how degenerate youth no longer use capitals and punctuation when writing. At least that’s what I did over lunch today with a few middle aged friends.

This is what old people talk about over lunch: how degenerate youth no longer use capitals and punctuation when writing. At least that’s what I did over lunch today with a few middle aged friends.

This is especially important to me because I’m in the business of selling clear writing. Having done so for many years, this much I know: the clearer you write, the better chance you have of avoiding confusion and getting what you want.

A few years ago, a recent college graduate and aspiring writer emailed me to ask for help in getting a job. He used no capitals, punctuation, paragraphs—let alone line breaks. It was just one huge blob of text. Continue reading…

Courtesy Shutterstock

Some of my clients have recently asked how to address coronavirus uncertainty in their immediate writing and content marketing plans.

While I don’t have all the answers, these seem to be the most common approaches: Continue reading…

The following was updated and adopted from a recent hired-speech I gave to a group of 50 CEOs and partners at the headquarters of NEA, the world’s largest venture capital firm.

Since 2005, I’ve written for half of the top 20 U.S. media and dozens of Fortune 100 companies as a seasoned writer-for-hire, content marketer, and best-selling author. From those experiences, this is what I know for sure: marketing is the way you let people know you exist. Content marketing is the ongoing explanation for why they should care.

Since 2005, I’ve written for half of the top 20 U.S. media and dozens of Fortune 100 companies as a seasoned writer-for-hire, content marketer, and best-selling author. From those experiences, this is what I know for sure: marketing is the way you let people know you exist. Content marketing is the ongoing explanation for why they should care.

As a discipline, branded journalism, thought leadership, and executive editorial is important, because it allows companies to persuade highly-informed buyers in an increasingly noisy world. Not only is it the fastest growing marketing budget, it’s also the most effective for satisfying search demand, engaging audiences, and satiating a buyer’s need to read and inform themselves before making a purchase.

What surprises people most that engage me? Here are the top five: Continue reading…

I recently read a thought-provoking essay by James Pogue on the rise of long-form articles that are later optioned into feature films and narrative-driven books, sometimes to the tune of several million dollars, as was the case with Argo, a movie that was based on a previously published Wired article.

I recently read a thought-provoking essay by James Pogue on the rise of long-form articles that are later optioned into feature films and narrative-driven books, sometimes to the tune of several million dollars, as was the case with Argo, a movie that was based on a previously published Wired article.

As Pogue seemingly sees it, this new economy of article-to-film adaptations turns previously idyllic literature into modern day “trash,” which is as harsh as it is inaccurate. For example, Say Nothing, a book written by the New Yorker’s Patrick Keefe and based on his previously published articles, is hardly trash for soon becoming a TV series. In fact, the book is phenomenal and proof that great authors and their stories deserve to be told across as many mediums and adaptations as possible, in an effort to reach as many people as possible—even ones that don’t like to read books or long-form articles.

On the whole, it seems like Pogue is just bemoaning change. Continue reading…

Me at my desk courtesy Lindsey Snow

I’ve been a professional writer since 2005 and a full-time writer since 2007. I moonlighted for a couple of years before transitioning to a full-time freelancing journalist, a “calling” I continue to this day.

Since then, these are some of the most frequently asked questions I get from aspiring writers or otherwise curious email inquires:

How do you become a self-employed writer?

My advice: write everyday and ask 50 people if they will publish your best work. If they all say no, ask 50 more and so on. This never fails but most writers will never do this and therefore go unpublished and unpaid. Usually I don’t even have to ask 50, but in two exceptional cases, I asked over 100 before someone said yes: My first story for Wired Magazine about college footballcomputers and my first travel column for Paste Magazine. Both were huge wins for my career and would have never happened had I quite after asking just 50. The harder you work, the luckier you get. (See also: How to succeed: Don’t quit until everyone in the room tells you “no”)

Is it actually possible to make a decent income at home and support a family by being self employed writer?

Yes. I’ve worked from home for the last 15 years, make a good income, and have six mouths to feed (wife and five children). In my experience, successful self employment requires persistence, low overhead (i.e. low maintenance lifestyle), extra emergency savings, and a willingness to sell your craft in addition to the craft itself. Self employment isn’t for everyone, but it can be done and is remarkably rewarding.

Continue reading…

I’ve worked a number of different jobs since first entering the workforce at the age of 16. (Before that, I unofficially worked as a lawn mower, paperboy, and child laborer from time to time.)

I’ve worked a number of different jobs since first entering the workforce at the age of 16. (Before that, I unofficially worked as a lawn mower, paperboy, and child laborer from time to time.)

In order of appearance, I’ve worked as a fried chicken cook, warehouse manager, youth soccer coach, cell phone clerk, corporate travel agent, web designer, blogger, and (for the last 13 years) a writer-for-hire.

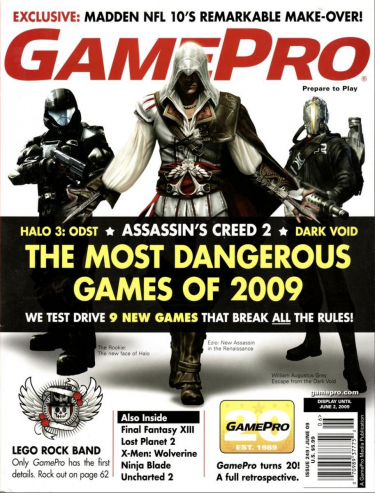

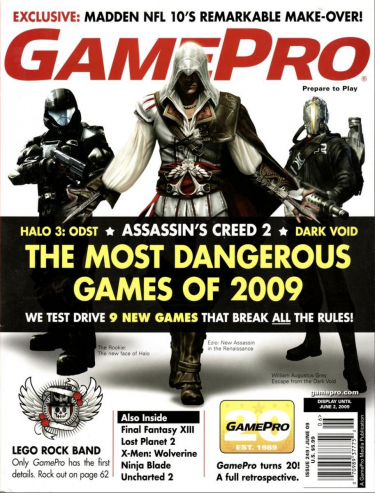

That last job really feels more like a calling than work, however, and within that category I’ve written a lot of different things. One of my favorite things was answering reader letters at a now defunct print magazine called GamePro. (Fun fact: I started writing as a game blogger before transitioning to tech, trade, and travel journalism.)

At the time, I was their news editor, which meant I mostly produced and managed a small team of three daily writers, myself included. The managing editor then took the best of said news for republish in the monthly print edition. Continue reading…

Me hiking the Inca Trail

Here’s something you might not know about my work as a writer: 30-40% of my time is spent asking people if I can write for them, while the remaining 60-70% is spent on actually writing.

In other words, I’m either a writer who knows how to sell or a salesman who knows how to write. Consequently, I would’t have survived the past 15 years if I hadn’t asked thousands of people each year to let me write for them. I would have wilted long ago had I listened to the few rouge naysayers that rudely tell me to get lost sometimes.

Case in point: of the hundreds of emails I send on a monthly basis, the vast majority are ignored. Continue reading…

Not long ago, I wrote a seemingly simple story that forever changed the amount of adventure I’ve been exposed to ever since.

For years leading up to that moment, my wife pleaded with me to take her and our kids to Disneyland. Although I went there as an eight year old boy with my family, I remember enjoying nearby Huntington Beach better than I did the actual park. So I told myself in the ensuing decades that Disney was a tourist trap and the great outdoors were the place for me.

Turns out, both man-made and natural wonders are for me. I probably wouldn’t have learned that truth, however, if it weren’t for my wife’s sage approach in tricking me to give The Happiest Place on Earth a fair shake. “Blake,” she said. “You could write about your experience—review it, report on how much you hate or love it.”

That’s all I needed to hear. Continue reading…

Derek Buck in 2015 overlooking the Great Smoky Mountains of Tennessee

I’ve never stayed in bed all day. At least not for mental reasons.

Thanks to the optimistic and high-energy genes I was gifted at birth, not to mention some healthy lifestyle habits (regular exercise/activity, balanced diet, lots of sleep, an appetite for reading, and scheduled relationship time), I’ve never felt depressed for more than a few hours at most.

So it’s difficult for me to relate and empathize with those who struggle with depression. I’m not saying that depression is invented. Not at all. But I am saying that it’s difficult for me to identify with or understand depression because I’m wired so differently.

My friend Derek Buck, on the other hand, knows depression all too well. I’m not sure if he’s up to his knees or up to his neck at the moment, but his excellent writing on the subject has increased my sympathy. Continue reading…

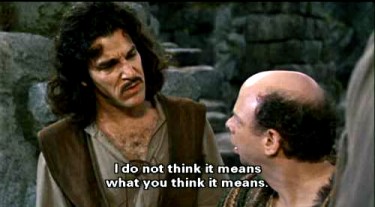

“The Princess Bride” 20th Century Fox

As a writer, I sometimes get reader mail.

Most of it relates to typos. Some of it relates to disagreement or additional viewpoints. On occasion, I even get fan mail—how lovely.

As for typo-related mail, most of that is really nice. “Hey, Blake. Enjoyed your story on [insert popular story here]. Noticed a typo, however, and thought I’d share.”

Some of it gives me the benefit of the doubt. “Hi, Blake. Perhaps your spellcheck mistakenly changed ‘espoused’ to ‘expelled’?”

“No, kind reader,” I’ll reply. “My bad diction stuck again. Thanks for keeping me honest.”

Still, some of the mail I receive is unforgiving. As if my mistakes should disbar me from contributing to mainstream media. As if I should master English before using it to articulate a point, tell a story, answer a question, or inspire change. Continue reading…

Courtesy New Line Cinema

“Hi, human. I sell this thing (in my case writing) for a living because I believe in it. It’s benefited myself and others you may know. Are you the right person to pitch? If no, do you know someone who is? If yes, is now a good time?”

I’ve been writing full time for 10 years now. Much of that time, if not half of the time, is spent asking people if I can write for them. In that sense, I’m either a writer who knows how to sell, or a seller who knows how to write.

Either way, I’ve followed the above pitch for the last decade. I don’t know if it’s the best sales approach, but it’s worked alright for me, and it’s one I feel is the most respectful.

Know a better way?

As someone who’s written hundreds of articles for fancy publications, I’m often asked the best way to land free publicity.

Outside of knowing when you have truly have something that’s noteworthy and knowing which audiences are most likely to find your something relevant, my colleague Josh Steimle recently wrote about the subject for Entrepreneur; specifically how to get great PR in 15 minutes per day.

Josh was kind enough to interview and quote me in the article. This is what I said: “Indirect PR pitches are the best way to increase your chances of a media placement. Rather than talking about yourself, explain a larger trend that might interest the journalist or publication you’re pitching, complete with stats, anecdotes and data.

“Your contribution should be only part of the story. Doing so not only makes the press’s job easier but demonstrates greater objectivity, further increasing your chances of a placement.”

In my experience as someone being pitched, that approach leads to a lot more placements.

Since we’re on the subject, now go watch Ace in the Hole, All The Presidents Men, State of Play, and Spotlight—all good if not remarkable movies on journalism.

I haven’t read George Orwell‘s six rules for writing since 2005, the year I started blogging and freelancing for Aol. Today Sarah Stanley reminded me of them, and I think they’re tops. Tops, I say!

- Never use a metaphor, simile, or other figure of speech you are used to seeing in print.

- Never use a long word where a short one will do.

- If it is possible to cut a word out, always cut it out.

- Never use the passive where you can use the active.

- Never use a foreign phrase, scientific word, or jargon if you can think of an everyday English equivalent.

- Break any of these rules sooner than say anything outright barbarous.

Numbers 2–5 have served me well in my career (i.e. concise language that everyday humans can understand). I’m guilty of number one, however. When on deadline adages accidentally spill sometimes.

I’m mixed about number six. Although admitedly the more noble thing to do, snark, harsh criticism, and emotional writing helped me find an audience early in my career. It’s cheap but it works. Maybe four out of six is good enough.

Twentieth Century Fox

When I was nine years old, I saw Big starring Tom Hanks. It’s a movie about a boy doing young-at-heart things in a grown-up’s body. That and being employed to have an opinion on (i.e. review) toys.

At the time, I thought it was the coolest movie ever made. I still think it’s pretty darn cool.

In reality, my work as a writer over the last decade is not unlike protagonist Josh Baskin’s. I get paid to have an opinion and ask a bunch of questions. I tinker with ideas, learn from those who are smarter than me, and slay the dragon of misinformation with research as my shield and a keyboard as my sword. Continue reading…

courtesy image

I recently finished Highbrow’s excellent 10-day course on inventions that changed the world.

In keeping score, half of the cited inventions quickened the sharing of information (writing, printing press, telephone, personal computer, internet). A third hastened our transportation (steam engine, automobile, airplanes). One marginalizes or maximizes physical dominance, depending on who owns more of it (gunpowder). And the last one lengthens our days (light bulb).

Interestingly, every one of these inventions involve some element of speed. The speed of a bullet. The speed of light. The speed of travel. The speed of knowledge. That’s why the world moves at an increasing rate. Our greatest inventions all involve speed.

Even this century’s greatest inventions largely involve speed. How fast you can get new or old music to your ears (iTunes, Spotify). How fast you can get answers to questions (Google). How fast you can connect with friends and family (Facebook, SMS). And how fast you can see the latest cat videos (YouTube).

Of course, many of these inventions involve size, frequency, and power. But when it comes to bigger, stronger, better, and faster—always bet on faster. It’s the future. And it’s likely what the “next big thing” will do more than others.

Hemingway aboard his boat off the coast of Cuba (1950)

As compiled by Highbrow:

- “The best way to find out if you can trust somebody is to trust them.”

- “The world breaks everyone, and afterward, some are strong at the broken places.”

- “I like to listen. I have learned a great deal from listening carefully. Most people never listen.”

- “Happiness in intelligent people is the rarest thing I know.”

- “I drink to make other people more interesting.”

- “As a writer, you should not judge, you should understand.”

See also: My review of Old Man and The Sea

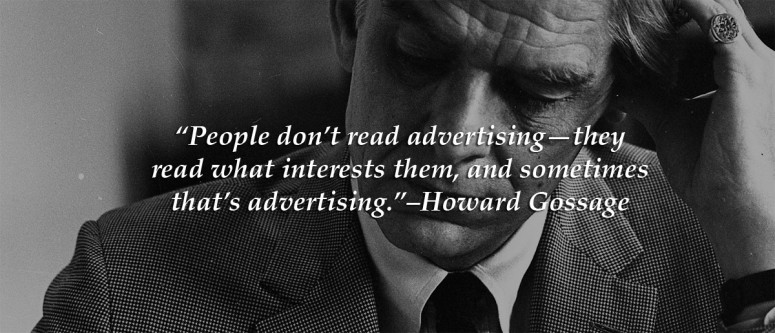

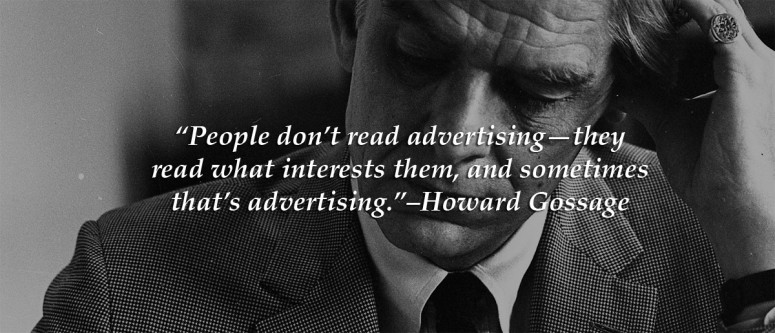

Howard Gossage was revered for his copywriting skills

Most people don’t know the difference between copywriting and editorial copy. I write the latter, which is generally understood by plebians as long-form “magazine articles.” The former is short-form and widely used in advertising and marketing to persuade someone to buy a product or influence their beliefs.

In any case, I usually don’t copywrite in a technical sense. I sometimes get asked to but usually decline. Unless, of course, Nike asks me to, which they did last year. Here is that story. Continue reading…

courtesy frank bourassa

What a story. What a character.

Wells Tower writes for GQ: “Frank paid a few visits to the U.S. Secret Service’s website, which, handily, offers an in-depth illustrated guide to serial numbers, watermarks, plate numbers, and all the other fussy obstacles to the counterfeiter’s art. ‘I thought, if I’m going to do this, I’ll go big or go home.'”

At the turn of the decade, the Canadian ended up printing more than $200 million in twenty dollar bills — an elephantine amount compared to most counterfeiters. “If he’d printed a measlier number of millions, he would have lacked a big chip with which to bargain for his liberty,” explains Tower. “He would certainly have been jailed longer. In other words, had Frank not gone big, it could have been quite a long time before he’d have been free to go home.”

Superb read. I highly recommend it.

courtesy: snow family

I don’t remember everything I read this year. But excluding short-form literature, these are the books and essays that impacted me most: Continue reading…

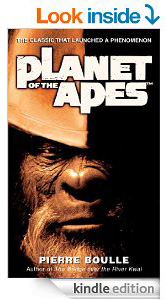

I’ve been working my way through some of history’s best-rated science fiction novels. And “no,” I don’t distinguish sci-fi from fantasy.

I’ve been working my way through some of history’s best-rated science fiction novels. And “no,” I don’t distinguish sci-fi from fantasy.

Overall, I find the technical language of books such as Hyperion, Shockwave Rider, and others with ridiculous covers—the kind Gentlemen Broncos makes fun of—too distracting to enjoy. Reading them feels like work. It’s almost as if the author wants me to decipher or decode the language before understanding it. It’s why I abandon many of these books, including The Hobbit. After all, I read to enjoy or educate myself—not learn a fictional language.

When they’re not using overly technical and distracting language, sci-fi novels often finish in confusing or unpoetic form, as is the case with Ender’s Game, an otherwise clever book. Now, I haven’t completely given up on the genre. I still have Dune, Starship Troopers, 10,000 Leagues Under the Sea, A Hitchhiker’s Guide to The Galaxy, and others on my list.

My faith in the genre skyrocketed today, however, after reading the first chapter of Planet of the Apes. It’s one of the best opening chapters I’ve read of any genre. It’s so captivating, I dare any imaginative mind over the age of 10 to read the first chapter and desist. It’s humanly impossible. Try it yourself if you don’t believe me, for free even.

That’s how you pull someone into a novel. Bravo, Pierre Boulle.

UPDATE: After finishing the book, I now regard Planet of the Apes as masterpiece literature—from beginning, middle, to the very ironic ending. Five stars out of five.

Wikimedia Commons

I got an unexpected royalty check from Denmark last month. Apparently some Dane liked one of my stories enough to make a bunch of copies for their organization to read. In route through foreign and U.S. copyright law, the specific story and organization that used it were lost unfortunately. But I’m grateful just the same — for the recognition as well as compensation.

Thanks, Denmark.

Kwekwe/Wikimedia

Five years ago, I “pivoted,” as they say in business. I went from writing feature stories primarily for top 20 news media to writing features stories for Fortune 500 companies as an embedded journalist and content advisor.

Landing a new client typically goes like this: They like my pitch and ask for more info. I send it to ’em. We talk. They like what they hear and think I can grow their audience with a fresh voice.

Over time, however, some of those clients let that voice rot. Continue reading…

I don’t know the scientific name, but I’m one of the lucky creatures that possesses an insatiable curiosity. As such, I use the Internet not only for work-related and entertainment purposes; I use it to satisfy every conceivable whim I encounter within my immediate environment on any given day.

I don’t know the scientific name, but I’m one of the lucky creatures that possesses an insatiable curiosity. As such, I use the Internet not only for work-related and entertainment purposes; I use it to satisfy every conceivable whim I encounter within my immediate environment on any given day.

For example, I often ask myself, “I like this song—I wonder where this band is from?” Or, “What other films has this director made?” Within seconds, Wikipedia has the answer. Last week, I overheard someone mention the country of Chad—a mystical place in west Africa. “Why haven’t I ever heard of this place?” I thought to myself. An hour later—thanks to Google—I was entrenched in all things Chad and was prepared to write an introductory discourse on the republic to attentive undergrads.

But as with all things in life, too much of anything is unhealthy. Except for maybe air guitar, chocolate cake, and dancing. But I digress. The trouble is we’ve reached a point with personal technology that it is so accessible, so immediately gratifying, and so demanding that digital indulgence is no longer just affecting information junkies like me. It’s affecting everyone. Continue reading…

A long-time Smooth Harold reader — and by long-time I mean four days — writes:

A long-time Smooth Harold reader — and by long-time I mean four days — writes:

Dear Smooth Harold,

I’m looking forward to the book you’re writing, but your fans want to know: What technology are you using to write a book about life/tech balance?

Yours in blogging,

David Cole

Cambridge, Mass.

Hi David. I’m writing the book in iA Writer. I’ll also require electricity to turn my computer on, an internet connection, and working plumbing. Does that answer your question?

As for the book, I’ll be launching a website, newsletter, and maybe even a podcast soon with sample chapters and the process I’m going through to ensure the book gets maximum visibility (i.e. the best agent, publisher, and distributor my idea can buy). So stay tuned. And by that I mean keep refreshing this page every 30 seconds for the next several weeks.

Thanks for writing.

If there’s one writing habit I simply adore, it’s seeing a writer use “back in” when referencing previous years or months.

If there’s one writing habit I simply adore, it’s seeing a writer use “back in” when referencing previous years or months.

For example: “Back in 1845…” or “Back in December.” In such instances, the leading “back in” solidifies my otherwise horrible sense of time. Without that “back in,” I’d be completely lost.

Just today, reading a cryptic “In 1997” left me utterly confused. Since I have no concept of past, present, or future tense verb usage, I wasn’t 100% certain the writer was referencing history.

Worse is when a concise writer references a previous month without the oh-so-enlightening “back in.” After all, it’s not like the reader can assume you’re talking about a previous month, especially since you didn’t also reference a year. Case in point: Is “In July” talking about past July or next July? It’s ambiguous. I mean, next we’ll be asking writers to say “next” when referencing the future. It’s unheard of.

So remember writers: Never assume a reader understands chronology. As such, always say “back in” when referring to the past. It’s not wordy or presumptuous at all.

This is what I emailed to him earlier this year:

This is what I emailed to him earlier this year:

If you enjoy the effort of doing something more than the result, you will be good at whatever you decide to do.

If you enjoy the effort of doing something more than the result, you will be good at whatever you decide to do.

This is what old people talk about over lunch: how degenerate youth no longer use capitals and punctuation when writing. At least that’s what I did over lunch today with a few middle aged friends.

This is what old people talk about over lunch: how degenerate youth no longer use capitals and punctuation when writing. At least that’s what I did over lunch today with a few middle aged friends.

Since 2005, I’ve written for half of the top 20 U.S. media and dozens of Fortune 100 companies as a seasoned writer-for-hire, content marketer, and best-selling author. From those experiences, this is what I know for sure: marketing is the way you let people know you exist. Content marketing is the ongoing explanation for why they should care.

Since 2005, I’ve written for half of the top 20 U.S. media and dozens of Fortune 100 companies as a seasoned writer-for-hire, content marketer, and best-selling author. From those experiences, this is what I know for sure: marketing is the way you let people know you exist. Content marketing is the ongoing explanation for why they should care. I recently read a

I recently read a

I’ve worked a number of different jobs since first entering the workforce at the age of 16. (Before that, I unofficially worked as a lawn mower, paperboy, and child laborer from time to time.)

I’ve worked a number of different jobs since first entering the workforce at the age of 16. (Before that, I unofficially worked as a lawn mower, paperboy, and child laborer from time to time.)

I don’t know the scientific name, but I’m one of the lucky creatures that possesses an insatiable curiosity. As such, I use the Internet not only for work-related and entertainment purposes; I use it to satisfy every conceivable whim I encounter within my immediate environment on any given day.

I don’t know the scientific name, but I’m one of the lucky creatures that possesses an insatiable curiosity. As such, I use the Internet not only for work-related and entertainment purposes; I use it to satisfy every conceivable whim I encounter within my immediate environment on any given day. A long-time Smooth Harold reader — and by long-time I mean four days — writes:

A long-time Smooth Harold reader — and by long-time I mean four days — writes: If there’s one writing habit I simply adore, it’s seeing a writer use “back in” when referencing previous years or months.

If there’s one writing habit I simply adore, it’s seeing a writer use “back in” when referencing previous years or months.